For this phase’s

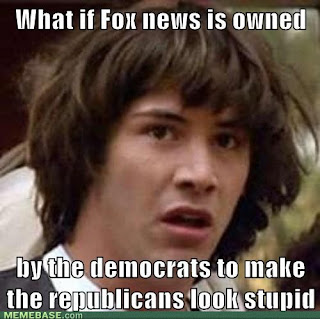

post I want to take us back to Postman and his stern apprehension over the growth

of television (and the one-way media channel) and the temptation to “amuse

ourselves to death” – what he deems “information glut.” It was surreal to read “Crap

Detecting” only to realize his predictions have come true. Throughout the

article and the video James posted, I couldn’t help but think of Robert Kubey’s

work with media literacy, which entails “critically analyzing media messages,

evaluating sources of information for bias and credibility, raising awareness

about how media messages influence people’s beliefs, attitudes and behaviors

and producing messages using different forms of media” (23). Kubey points out

that the US seriously lags behind all other English-speaking countries such as

Canada and Australia in offering critical media literacy as young as 5th

grade. It would seem that the US is doing a serious disservice to its youth by

pumping them full of technology they have no formal training in analyzing and

contextualizing and, therefore, designates media literacy as “an entitlement of

every citizen” (21). The question is, if the government is not willing to offer

such analytical training (and really, why would it, since it would undermine

myriad agendas and political manipulations), how do we create (I say create

because clearly we are not there yet) and sustain a democratic society in the

face of media bombardment (cue Simpsons’ dodgeball-obsessed gym teacher here)?

I’d like to “remix”

these two thinkers, who have a thirty-three year time difference in the

publication of their texts, and put them in direct conversation with one

another to see where we’ve been, where we presently are, and where we should

aim to be:

Kubey:

“Democracy, it is said, depends on an informed public” (“Media” 69).

Postman: “To the

extent that our schools are instruments of such a [democratic] society they

must develop in the young not only an awareness of this freedom but a will to

exercise it, and the intellectual power and perspective to do so effectively”

(1).

Kubey: “But if a

school is teaching critical thinking and not linking critical thinking to the

media world that so many students are spending upwards of six hours a day with,

they are leaving a potential gold mine unexplored” (“What Is” 23-24).

Postman: There

are men in power who “would prefer that the schools do little or nothing to

encourage youth to question, doubt, or challenge any part of the society in

which they live, especially those parts which are most vulnerable” (2).

Kubey:

“Politicians have become extraordinarily adept at using the media to their

advantage […] to the degree that the media are used to propagandize or

manipulate and interfere with the public being well-informed, is the degree to

which we need media education to be part of our schools’ civics and

social-studies classes” (“What Is” 24).

Postman: “Whose

schools are they, anyway. And whose interests should they be designed to serve?

[…] We believe that the schools must serve as the principle medium for

developing in youth the attitudes and skills of social, political, and cultural

criticism” (2).

Kubey: “the U.S. educational establishment is still too often

mystified as to how to retool and retrain to educate students and future

citizens for the new realities of communication” (“Media” 76).

Postman: “Things

that plug in are here to stay. But you can study media with a view toward

discovering what they are doing to you […] Certainly it is unrealistic to

expect those who control the media to perform that function. Nor the generals

and the politicians. Nor is it reasonable to expect the “intellectuals” to do

it, for they do not have access to the majority of youth. But school teachers

do, and so the primary responsibility rests with them” (8, 13).

So, in closing,

it would seem that we are not only literacy sponsors, but we are also media

literacy sponsors: a tough task to take on. How are you responsibility

sponsoring media literacy in your classrooms, and how does our tendency to

engage students’ interest with technology and digital texts play into Postman’s

concerns?

Works Cited

Kubey, Robert.

“Media Literacy and the Teaching of Civics and Social Studies at the Dawn of

the

21st Century.” American

Behavioral Scientist 48.1 (2004): 69-77. Print.

-------- “What

is Media Literacy and why is it So Important?” Television Quarterly 34.3/4

(2004):

21-27. Print.

Postman, Neil

and Charles Weingartner. “Crap Detecting.” Teaching

as a Subversive Activity.

Brooklyn:

Delta (1971). 1-15. Print.